Critique: “Things I wish I learned in Engineering School”

A friend of mine recently pointed me to an interesting article by Rick Cattell, distinguished engineer at Sun microsystems. I had never heard of Rick but he sounds knowledgeable and had good insights to share in a couple of different areas: successful companies, technical innovation, successful products and career issues, all of which are like crack-cocaine to me because, well, I am very interested in these topics. My thoughts on some of these:

1. Rule 1: Almost all organizations try to do too many things

I’ve seen it happen, but I disagree here with the “Almost all” part. From the 5 or so companies I have worked at, only 2 were trying to do what I’d categorize as “too many things”. The rest were/are about right in my opinion. Sure, the resources were scarce (but aren’t they always – if they’re not you have a problem). Besides, if you don’t have enough things to do as a company, you probably need to reconsider whether you’re in the right business. On the other hand, if the number of projects is out of control and the engineering team is overworked, that probably is a sign that the product team needs to get it’s act together (prioritization/MVP is one of the key principles behind good product, after all).

2. Rule 2: 1% of leaders are responsible for most successes

True, but again I think the “1%” is just a hypothetical number used for effect, because I don’t see a “meaningful” study or analysis backing that number up. That said, I agree with the sentiment here. Good leaders are hard to find. In fact, in my opinion, a true leader is someone who encourages and stands by his team through thick and thin, is willing to face the worst if the shit hits the fan, and is happy to share credit when it is due. He truly cares about his team and people and realizes that people come first. He has the market and technical vision and knows how to mentor and guide his team to get there. I have come across a few leaders who meet all of these criteria, but the odds of finding someone with all of these qualities is slim.

3. Rule 4: A suboptimal decision is almost always better than none & The reverse problem (ready shoot aim) is rare.

This is a sign that either:

- there are too many layers of management involved in making a decision (consensus oriented management, as Rick puts it), or

- the culture is driven more by fear of what won’t happen if the company does not meet its goals (versus being driven by an excitement for what would happen if the company does meet its goals), or

- the people on your team simply don’t have that killer instinct that few people are born with, or

- The company doesn’t have (or reward or encourage) a ready-shoot-aim kind of culture, which is critical if you want to be a force in today’s hyper-competitive market

It could also be a combination of these that’s making your organization drag its feet.

In general, I believe that getting out there fast (and with a product that is good, but not perfect), is far better than waiting for months getting a perfect product out there.

4. Rule 5: Trust in an organization is inversely proportional to distance

True. Which is why companies like Facebook are proactive in adopting “open” environments and “flatter” organizations. Trust evaporates with every new layer you add. It’s important that your people feel empowered to share things with you that they wouldn’t otherwise share if you were “too far up the chain of command”. One way for a leader to foster that kind of culture is to put himself “in the trenches” with his team.

5. Rule 7: Engineers follow the leader

Doesn’t everybody?!

Also true – the “leader” doesn’t necessarily have to be on the org chart.

6. Taylor’s law: You need more pigs than chickens

It all comes down to a sense of ownership. In my experience, actual ownership typically doesn’t matter as much as does “the feeling” of ownership. So yes, “skin in the game” promotes success. In general, you want to engender a culture of competition and collaboration, and a feeling of “owning this together” versus a “not my fault this happened” culture.

7. Lampson’s Law: Most research and startups will not succeed, and Joy’s Law: Innovation will happen elsewhere

These are obvious imo, and don’t need to be elaborated on.

8. Rule 29: You have to sell your ideas

True, because we’re all marketers now. When it comes to projects that see the light of day versus those that don’t, selling your ideas is an important part of the equation. It’s a bitter pill that needs to be swallowed, especially by individuals and groups within the company that feel that they “shouldn’t have to sell their ideas” to see them on the roadmap. Simply not true.

9. Rule 41: Know your customer

This should be rule #1 imo. Winners do eat their own dogfood. One of the things I learned from reading books on the #leanstartup, is to focus on insights versus results. It is far more valuable to know why a customer bought something (because you can then repeat what you did or didn’t do) versus having 2 customers buy something but not know why. One of the core things I believe in is: ABT = Always Be Testing (ideas, code, copy, banners, promos, ads)

10. Rule 42: Being first is more important than being best

This goes hand-in-hand with Rule 4: A suboptimal decision is almost always better than none & The reverse problem (ready shoot aim) is rare.

Also true that the most popular product or technology is often not the best.

11. Kannegaard’s law: Physics overcomes fine print

You certainly cannot change natural tendencies, but you can build your products and incentives to take advantage of those natural tendencies.

12. Prioritize tasks every day, every week and every year

Because if you don’t, you’re not going to be focusing on your most important issues, and you could be going down the rabbit hole of working on something that does not matter, or can be outsourced, so you can focus on the things that do matter that you are uniquely qualified for.

13. Rule 64: Don’t get too good at what you don’t like doing

Commit this cardinal sin and you’re doomed to a professional life of unhappiness. This goes hand in hand with:

- Being able to say no to work which you can do but would rather not do,

- Making sure you’re good at the work you DO want to do and want to be known for.

How to Amplify Social Proof to increase your persuasiveness

This is part of the ‘Lessons in Persuasion’ series. Each post is a concise blurb on how you can be more persuasive in your interactions with people. If you have any thoughts to share, please leave a comment or response below – or contact me.

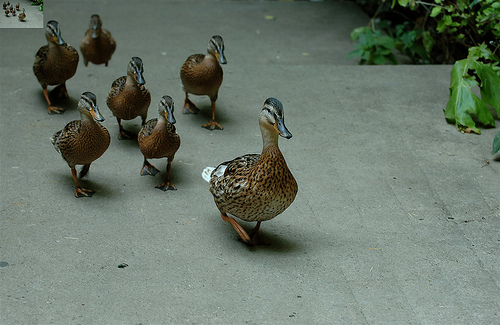

In the last post we saw that Social Proof can have a profound effect in helping increase your persuasiveness . It’s a known fact that human beings are social animals, and it’s in our nature to do what others are doing, or let others’ actions guide our own. However, when 2 (or more) groups are competing with each other in an attempt to sway a common target to their divergent points of view, which group is likely to have the most profound effect in persuading the target? Conversely, which herds are people most likely to follow? The short answer is, the herd that they perceive to be most like them.

People are more influenced by a herd that they perceive to be more like them (a herd that looks like them, acts like them, has shared a similar experience, etc). There’s no rational reason to believe that a person that has experienced the same thing you are going through now would have an influence on your behavior, even if you share nothing in common with that person – but it’s observed to be true, and it happens.

It is usually beneficial for us to follow the behavioral norms associated with the particular environment, situation or circumstance that most closely matches our own. When you’re at a public library, you typically tend to follow the norms of other library patrons, by quietly browsing through the books and whispering when you need to say something. You certainly do not act like you’re at a bar, crushing books against your forehead.

How can we utilize these principles? We already saw the importance of client testimonials in trying to sway people’s opinions in your direction. To take things a step further, the more similar the person giving the testimonial is to the target audience, the more persuasive the message becomes. It follows that it becomes all the more important to decide which testimonials to show to a prospect based on the prospect’s own situation or circumstance, NOT the one that you’re the most proud of.

If you’re pitching to the owner of a social media company, he’d be more likely to buy into your point of view or purchase your product or service if you demonstrated how your software had helped other social media companies (versus how your software has helped a fortune-100 company in the transportation sector).

The thinking goes like this:

- “If others like me have gotten good results with this product, then it should be right for me, too“.

- “If others like me are doing this, then I should probably do it, too“.

How to use Social Proof to increase your persuasiveness

This is part of the ‘Lessons in Persuasion’ series. Each post is a concise blurb on how you can be more persuasive in your interactions with people. If you have any thoughts to share, please leave a comment or response below – or contact me.

Other’s people behavior is a powerful source of social influence, and has a strong effect on the actions we take and decisions we make, whether we like to admit it or not. In fact, when a group or social psychology researchers asked people in their studies whether other people’s behavior influenced their own, they were absolutely insistent that it did not. Yet, it’s a well known fact that in general, people’s ability to understand what affects their decisions and behavior is surprisingly poor.

In one such social experiment, an assistant of one of the researchers stopped on a busy New York City sidewalk and started staring at the sky for about a minute. The majority of passers-by simply walked around the man without bothering to see what the man was staring at. However, they then added 4 other men to the group, and in an instant, the number of passers-by who joined them more than quadrupled.

Social proof has immense power – it can pay huge dividends in your attempts to persuade others to take a desired course of action. However, the means of communicating the same should not be underestimated. Saying something like, “Hey you, be a sheep and join the herd” is not going to have people respond favorably to your request. Instead, you may try something like “Join countless others in helping save the environment”, or, taking a page from McDonalds’ book, “Billions and billions served”. In the same vein, you are more likely to “like” something on Facebook if others have already “liked” it.

So how can you use social proof in your work life? Use it to tout top selling products and services, with impressive statistics on their popularity. Always ask for testimonials from satisfied customers and clients, especially when pitching to potential clients that are “on the fence” about the benefits your product or service can provide. If you’re interviewing for a job at a company you really want to work for, saying that you have competing offers from other high profile companies can greatly increase your desirability and leverage when negotiating an offer. Of course, I don’t condone lying to get what you want – that rarely works (to be honest I wish I was a better liar, but I’m not).

The long and the short of it is this – if we perceive something to be in high demand and that others are interested in it, we are far more likely to be interested as well (whether or not that’s true is another matter entirely).

Inconvenience your target to increase your persuasiveness

This is part of the ‘Persuasion’ series. Each post is a concise blurb on how you can be more persuasive in your interactions with people, and it’s taken from stuff I’ve learned + read. If you have any thoughts to share, please leave a comment or response below – or contact me.

“That which we obtain too easily, we esteem too lightly. It is dearness only which gives everything its value.”

-Thomas Paine

Colleen Szot – remarkably successful writer in the paid programming industry, changed 3 simple words to make sales of her product skyrocket. She changed the call-to-action line “Operators are waiting, please call now” to “If operators are busy, please call again”. This seemingly simple change utilizes the power of the principle of social proof, which says that if we are uncertain about a course of action, we tend to look outside ourselves and to other people around us to guide our thoughts and actions. In this example, we end up imagining high demand (tons of potential customers and operators that are too busy to pick up the phone because they’re taking other calls).

The takeaway from this lesson:

Make your target audience work for it. We only value what we struggle for — and I speak from experience on this one. What is “granted” to us– we take “for granted”, hence the term “to take for granted”. Making something too easy to attain diminishes your value. At the same time, you don’t want to put up too much of a challenge – or so many roadblocks that your audience gives up, thinks it’s unattainable, or that the effort involved is not worth the reward.

The ‘Lessons in Persuasion’ Series

I decided a while back that I wanted to teach myself how to become more persuasive. The benefits don’t need to be stated – being more persuasive can help you at work and in your personal life. Need to convince your interviewer to give you the job? Need to convince your spouse to take that vacation you’ve been wanting so bad? Need to motivate your employees to put in extra time to get a project you really want out the door? Need to convince your teenage daughter to quit smoking? It’s your job to make them want to do it. But the question that has always been on my mind is, how? How do you make someone excited about doing what you want done?

If there’s one thing I have learned, it’s this – if you want someone to do something, you have to make them want to do it. It is YOUR JOB to make them want to do it, NOT THEIR’S. Approaching most things in life this way not only helps you stay accountable for your own successes and failures, but it also sets you up to be more likely to succeed.

Even if we think we’re pretty good at being persuasive, it never hurts to be reminded of the principles that work. Persuasiveness is a science, not an art – and it can be learned. If implemented the right way, can have a huge potential payoff. And don’t we all want that?

In this multi-part series, I’ll be sharing what I’ve learned through personal experiences and from books I’ve read or am reading. While I’m writing this primarily as a reference for myself – to remind myself of the principles that work (that I’m in the process of learning), I thought I’d share them with you at the same time.

The 10000 hour rule

This is part 2 of a series of posts on persistence being a key factor to success.

In my previous post we went over the Matthew Effect and how you can make use of it to win an edge over your competition and peers (In short, knowing how to capitalize on an initial edge and play to your strengths can make a huge difference. That said, nothing comes without effort, you have to work for it).

In this post I am going to go over a concept called the 10,000 hour rule. This term was coined by Dr. K. Anders Ericsson, a Swedish psychologist, in the early 90s. However, it was Malcolm Gladwell (Canadian journalist, speaker, staff writer for The New Yorker, and author of 4 New York Times Bestsellers) who brought everyone’s attention to the 10,000 Hour Rule in his book Outliers: The Story of Success. In his book, Gladwell claims that the key to success in any field is, to a large extent, a matter of practicing a specific task for a total of around 10,000 hours.

When Dr. Ericsson was originally researching this, he and his team divided students into three groups ranked by excellence at the Berlin Academy of Music and then correlated achievement with hours of practice. They found that the elite all had put in about 10000 hours of practice, the good 8000 and the average 4000 hours. No one had fast-tracked. This rule was then applied to other disciplines and Ericsson found that it proved valid.

From Wikipedia:

Gladwell claims that greatness requires enormous time, using the source of The Beatles’ musical talents and Bill Gates’ computer savvy as examples. The Beatles performed live in Hamburg, Germany over 1,200 times from 1960 to 1964, amassing more than 10,000 hours of playing time, therefore meeting the 10,000-Hour Rule. Gladwell asserts that all of the time The Beatles spent performing shaped their talent, “so by the time they returned to England from Hamburg, Germany, ‘they sounded like no one else. It was the making of them.'” Gates met the 10,000-Hour Rule when he gained access to a high school computer in 1968 at the age of 13, and spent 10,000 hours programming on it.

In Outliers, Gladwell interviews Gates, who says that unique access to a computer at a time when they were not commonplace helped him succeed. Without that access, Gladwell states that Gates would still be “a highly intelligent, driven, charming person and a successful professional”, but that he might not be worth US$50 billion. Gladwell explains that reaching the 10,000-Hour Rule, which he considers the key to success in any field, is simply a matter of practicing a specific task that can be accomplished with 20 hours of work a week for 10 years. He also notes that he himself took exactly 10 years to meet the 10,000-Hour Rule, during his brief tenure at The American Spectator and his more recent job at The Washington Post.

My take on it:

- I find concepts like this fascinating, especially if it has the potential to change my life for the better. Kudos to Dr. Ericsson for researching this problem and Mr. Gladwell for popularizing the message.

- 10,000 hours is roughly ~5 years of time at ~40 hours per week (full-time employment), and roughly ~10 years of time at ~19 hours per week (serious hobby). So if you want to achieve greatness in anything, make sure it’s one of these two (ideally it’s the former, but that’s not always the case – not everyone can turn their passion into gainful employment).

- To me, it’s well worth spending a few days (or even months) to decide whether the skill you’re going to focus on is worth the time investment. Especially when you’re just starting off. Is what you’re doing (or going to do) making you happy? Are you passionate about spending most of your time on this? Why are you doing it?

- To some people, it may be obvious from an early age, but for others like me, it wasn’t obvious.

- Michael Nielsen is skeptical (even critical) when he writes, “How can one match this level of devotion? 10,000 hours is a lot of time, and most studies have found that it requires 10 or more years to put in this time, given the other demands of life. Must we commit ourselves to 10 years of deliberate practice in a single area, or content ourselves with mediocrity?”

- To acquire mastery in an area, it’s not enough to just practice for 10,000 hours; the person practicing must constantly strive to get better. Someone who practices without pushing themselves will plateau, no matter how many hours they practice.

- While 10,000 hours could be an interesting way to measure mastery in any area, I agree with Michael Nielsen when argues that it’s a mistake to simply focus on building up 10,000 hours of deliberate practice as some kind of long-range goal. It is far better to focus on a set of skills that you believe are broadly important, and that you enjoy working on, a set of skills where deliberate practice gives rapid intrinsic rewards. Work as hard as possible on developing those skills, but also explore in neighboring areas, and (this is the part many people neglect) gradually move in whatever direction you find most enjoyable and meaningful. The more enjoyable and meaningful, the less difficult it will be to put in the time that leads to genuine mastery. The great computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra said it well: Raise your quality standards as high as you can live with, avoid wasting your time on routine problems, and always try to work as closely as possible at the boundary of your abilities. Do this, because it is the only way of discovering how that boundary should be moved forward.

- Most people are very good “starters”, but very poor “finishers”. Put another way, they get excited about something, get started with it, put a few hours/days/months into it, somehow convince themselves that it’s either going to fail or isn’t worth their time, and yes, inevitably quit. What a waste! To me this is worse than wasting money – or food – or water…because this time is never going to come back. Ever.

It is estimated that the vast majority of people barely make it through the first 2 chapters of any new book they pick up. That just amazes me.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I have been guilty of that very same thing on a few (okay, a number of) occasions, but I would (conveniently) argue that in my case I didn’t see much value in the books I decided to quit on, for it would have been a far better investment of my time to do something else. After all, time is your most valuable asset. - 10,000 hours of time is hardly a small investment – on the contrary, it’s a lifetime. But if you’re going to do something, you might as well aim at being the best at it. I’m going to cover a related concept called the “Superstar effect” in a future post.

What’s your take on the 10,000 hour rule? If you have an experience to share, leave a comment below.

What is the “Matthew Effect” and why it matters

![snail-race[1]](http://connecteev.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/snail-race1-300x199.jpg) The term Matthew Effect was first coined by Robert K. Merton, a Genius sociologist of Columbia, and it takes it’s name from the Biblical gospel of Matthew:

The term Matthew Effect was first coined by Robert K. Merton, a Genius sociologist of Columbia, and it takes it’s name from the Biblical gospel of Matthew:For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.

—Matthew 25:29, New Revised Standard Version.

The Matthew Effect is the notion that a small initial difference in performance of any 2 people will inevitably grow, because the person who is a little bit ahead will get so many more opportunities and advantages, that they will eventually end up being far ahead.

As an example by Malcolm Gladwell:

If you are a young boy, born in October, November or December who has goals to become a professional soccer or hockey player, the deck is stacked against you. There’s not much you can do – you should probably give up.

Despite Malcolm’s tongue-in-cheek comment, the truth is that an extraordinary number of hockey players are born in the first 3 or 4 months of the year. Why?

From an interview with Malcolm:

It’s a beautiful example of a self-fulfilling prophecy. In Canada, the eligibility cutoff for age-class hockey programs is Jan. 1. Canada also takes hockey really seriously, so coaches start streaming the best hockey players into elite programs, where they practice more and play more games and get better coaching, as early as 8 or 9. But who tends to be the “best” player at age 8 or 8? The oldest, of course — the kids born nearest the cut-off date, who can be as much as almost a year older than kids born at the other end of the cut-off date. When you are 8 years old, 10 or 11 extra months of maturity means a lot.

So those kids get special attention. That’s why there are more players in the NHL born in January and February and March than any other months. You see the same pattern, to an even more extreme degree, in soccer in Europe and baseball here in the U.S. It’s one of those bizarre, little-remarked-upon facts of professional sports. They’re biased against kids with the wrong birthday.

After checking out Malcolm’s Gladwell’s book, “Outliers,” and his explanation of why Canadian hockey players born early in the year have a big advantage, ESPN conducted a little study: They tallied up all the NHL players from this season who were born from 1980 to 1990. Sure enough: Many more were born early in the year than late. Here are the results.

| Month | Players |

| January | 51 |

| February | 46 |

| March | 61 |

| April | 49 |

| May | 46 |

| June | 49 |

| July | 36 |

| August | 41 |

| September | 36 |

| October | 34 |

| November | 33 |

| December | 30 |

We see exactly the same effects in school systems. The relatively younger kids in the class typically underperform the oldest kids – and that underperformance lasts into the college years. Kids born in the last 3 months of their age cohort in school are ~10% less likely to go to college than their peers.

The takeaways?

- Had the officials in charge of the hockey league just started a parallel league, with a cut-off in late summer – that could have leveled up the playing field, and taken advantage of talented hockey players that might have otherwise been at a disadvantage because of the month of year they were born.

- This example shows how profound of an effect encouragement and persistence can have on your success. The best people in a certain field tend to feed off of an incremental initial advantage over their peers and build on top of that.

- Talent is over-rated. You can plough through any disadvantages (real or perceived) with encouragement and persistence.

- If that encouragement is not externally available (and for the most part when you’re starting off with anything – a new skill, a new project, whatever – it’s generally not), it needs to come from the inside.

I’ll be covering this topic from a different angle, that is complementary to the notion of persistence being a key factor to success, in a future blog post.

Applying the economics of Comparative Advantage to Business and Product Decisions

Unless you’re an economics major or studied it in college, there’s a good chance that you haven’t heard of the law of Comparative Advantage. Even if you have, this post may still either serve as a good refresher if it’s been a while, or offer a different perspective and/or application of the concept as it relates to either: managing your time as a busy entrepreneur, or deciding what to focus on as a product owner so as to maximize your chances of product success.

It’s no secret that the laws of economics can be applied to problems spanning a range of topics, sectors and even industries, in many different ways. They can be applied to business, to management, managing/growing your personal finances, and to yes, even relationships. For the record though, I can’t say I agree with all of the applications of economics, in particular this one, where the author argues that as a woman, marrying for money is “the smart thing to do”, and goes so far as to say: “After all, passion fades, but mutual funds are forever.” Heh, whatever.

So, let’s see how we can apply one economic concept, called Comparative Advantage, to either of the following problems:

- An entrepreneur skilled in several areas with a limited amount of time and resources, and faced with the problem: “I have too much to do and too little time. Do I focus on product, hiring, marketing, investor relations, or split my time between them? How do I decide how much time to spend on each?” (after all, founders are, typically, gifted, multi-talented, versatile professionals)

- A product owner faced with the question: “I’m planning on launching a product that does x, y and z. I know of at least 3 competing companies that do x, y and z. Should I focus my product to do one of either x, y or z? Or all of the above? How do I decide what to do first, and how much time to spend doing that?”

But first let’s take a look at what the law of Competitive Advantage is, before we see how it can be applied to answer these two (rather common) questions.

According to Wikipedia, David Ricardo (1772–1823), was one of the most influential classical economists that ever was. He was also a member of Parliament, businessman, financier and speculator, who amassed a considerable personal fortune. His most important contribution was the law of Comparative Advantage, which states:

Let’s look at some examples (courtesy of Wikipedia) that demonstrate the immense utility of this economic law in simpler terms:

Example 1

Two men live alone on an isolated island. To survive they must undertake a few basic economic activities like water carrying, fishing, cooking and shelter construction and maintenance. The first man is young, strong, and educated. He is also faster, better, and more productive at everything. He has an absolute advantage in all activities. The second man is old, weak, and uneducated. He has an absolute disadvantage in all economic activities. In some activities the difference between the two is great; in others it is small.

Despite the fact that the younger man has absolute advantage in all activities, it is not in the interest of either of them to work in isolation since they both can benefit from specialization and exchange. If the two men divide the work according to comparative advantage then the young man will specialize in tasks at which he is most productive, while the older man will concentrate on tasks where his productivity is only a little less than that of the young man. Such an arrangement will increase total production for a given amount of labor supplied by both men and it will benefit both of them.

Example 2

Suppose there are two countries of equal size, Northland and Southland, that both produce and consume two goods, food and clothes. The productive capacities and efficiencies of the countries are such that if both countries devoted all their resources to food production, output would be as follows:

Northland: 100 tonnes, Southland: 400 tonnes

If all the resources of the countries were allocated to the production of clothes, output would be:

Northland: 100 tonnes, Southland: 200 tonnes

Assuming each has constant opportunity costs of production between the two products and both economies have full employment at all times. All factors of production are mobile within the countries between clothes and food industries, but are immobile between the countries. The price mechanism must be working to provide perfect competition.

Southland has an absolute advantage over Northland in the production of food and clothes. There seems to be no mutual benefit in trade between the economies, as Southland is more efficient at producing both products. The opportunity costs shows otherwise. Northland’s opportunity cost of producing one tonne of food is one tonne of clothes and vice versa. Southland’s opportunity cost of one tonne of food is 0.5 tonne of clothes, and its opportunity cost of one tonne of clothes is 2 tonnes of food. Southland has a comparative advantage in food production, because of its lower opportunity cost of production with respect to Northland, while Northland has a comparative advantage in clothes production, because of its lower opportunity cost of production with respect to Southland.

To show these different opportunity costs lead to mutual benefit if the countries specialize production and trade, consider the countries produce and consume only domestically, dividing production capabilities equally between food and clothes. The volumes are:

| Country | Food | Clothes |

|---|---|---|

| Northland | 50 | 50 |

| Southland | 200 | 100 |

| TOTAL | 250 | 150 |

This example includes no formulation of the preferences of consumers in the two economies which would allow the determination of the international exchange rate of clothes and food. Given the production capabilities of each country, in order for trade to be worthwhile Northland requires a price of at least one tonne of food in exchange for one tonne of clothes; and Southland requires at least one tonne of clothes for two tonnes of food. The exchange price will be somewhere between the two. The remainder of the example works with an international trading price of one tonne of food for 2/3 tonne of clothes.

If both specialize in the goods in which they have comparative advantage, their outputs will be:

| Country | Food | Clothes |

|---|---|---|

| Northland | 0 | 100 |

| Southland | 300 | 50 |

| TOTAL | 300 | 150 |

World production of food increased. clothes production remained the same. Using the exchange rate of one tonne of food for 2/3 tonne of clothes, Northland and Southland are able to trade to yield the following level of consumption:

| Country | Food | Clothes |

|---|---|---|

| Northland | 75 | 50 |

| Southland | 225 | 100 |

| World total | 300 | 150 |

Northland traded 50 tonnes of clothes for 75 tonnes of food. Both benefited, and now consume at points outside their production possibility frontiers.

Now how would we apply this concept to the 2 problems we looked at earlier?

For an entrepreneur with more things to do than there are hours in the day, it makes little sense to focus on anything other than the things he is best suited for. Now that might be sales, or product (but whatever that something is, it’s best if the entrepreneur didn’t stray too far from that job function, otherwise he wouldn’t be able to spend time on the things that only he uniquely can do relative to his teammates. This is especially true for the entrepreneur that is so experienced / talented that he is capable of doing the job of each of his direct reports better than they can). Of course, this ties in closely with delegating the right tasks to the right people, and hiring people that are smarter than you are.

Similarly, for a product owner looking to make a decision on whether to focus on product X, Y or Z (or all of the above), he must again, take a close look at what the team’s / company’s comparative advantages are (time to market, cost of development/production, man hours that would be required) in relation to its competitors. If the company projects that it could realize the lowest opportunity cost with product X in relation to products Y or Z and its competitors building out the same products, it should focus on building product X first. This is not to say that product Y and product Z don’t present sufficient incentives to be pursued. If the company possesses a clear comparative advantage if it were to build out product X, that’s what they should do first.

This argument does assume a number of things:

1. The team or company has a limited amount of resources, and doesn’t have the funds/manpower to proceed with developing X, Y and Z in parallel.

2. The product owner has already done his/her due diligence – run focus groups, analyzed the competitive landscape and done the requisite customer research before arriving at the conclusion that either one of product X, Y, or Z is the best path for the company to take at this point in time.

3. Neither of the companies already has a product X, Y, or Z, and these are possible products they are each considering.

Of course, the concept of Comparative Advantage has several applications, and we’ve only looked at a few examples, specifically how they relate to making business and product decisions. Needless to say, if you adopt this line of thinking into your everyday actions, it’s not hard to imagine how this could have a positive disruptive effect on the way you make most of your decisions.

On leadership.

Derek Sivers gave an interesting TED talk on leadership. Great video that really breaks down the process of starting a movement.

My notes:

- A leader needs the guts to stand out and look ridiculous (most of us know this already).

- But what really was the key takeaway for me was:

You must be EASY TO FOLLOW

What you do should be SO SIMPLE, it should be ALMOST INSTRUCTIONAL. - The first follower has a crucial role: He publicly shows everyone else how to follow. Being a first follower is an under-appreciated form of leadership. Like the leader, the first follower needs the guts to stand out and be ridiculed. The first follower TRANSFORMS a lone nut into a leader.

- The leader must embrace and nurture his first follower as an equal. This is where the leader should check his ego at the door – it should never be about the leader or the follower, it should always be ABOUT THE CAUSE.

- The second follower is the turning point – and it’s PROOF that the first follower has done well.

- NEW followers emulate followers, NOT the leader.

- As more people jump in and start following, it’s no longer risky to join in on the movement.

- Leadership is over-glorified. The leader may get all the credit, but it is the first follower that transforms the lone nut into a leader. There is no movement without the first follower.

- If you are not the leader, the best way to make a movement (if you really care) is to courageously follow and show others how to follow.

Here’s the video:

Using Psychology to make Product Decisions

In order to build successful products (products people use, products that are profitable, products that change the world), a product owner needs to think like the end-user or customer that would end up using that product.

Products that fail to inspire, motivate or entertain turned out that way because of one (or more) of the following reasons.

1. The product owner didn’t understand who the customer was. Clearly the worst possible scenario, because your product is doomed from the start.

2. The product owner did understand who the customer was, but wasn’t sure what his needs were.

3. The product owner understood the customer’s needs, but wasn’t able to come up with a viable solution, or worse, came up with a solution that did not meet his customer’s needs. As a result, almost nobody purchased the product.

4. The product owner understood the customer’s needs, but the solution he came up with was too complex, too expensive, or required too much effort from the end-user’s point of view.

1,2,3 are pretty serious problems, ones that should make you question the people you have put in charge of your product decisions and roadmap.

However, I want to address #4 here, because, it is a more common problem to have, and there’s a point I want to make.

Ever come across a product or website that was a pain to use? Like, you can never find the content you’re looking for, you need to click 10 links to even see what’s in your shopping cart, and so on? I can bet that at the time you were ready to pull your hair out, and you would rather shoot yourself over go back to using that same product again.

In most of these situations, the product owner hasn’t taken the time to REALLY think of his customer’s needs and requirements. By that I mean putting himself in his customers’ shoes, and looking at the product (price, product offering, user experience, whatever) from that perspective.

Well, easier said than done, right? Yes and no. A degree in psychology might just come in handy here, but there are simpler ways to get an accurate gauge of your customers’ needs.

1. If you do have customers, the solution is simple. Just ask them. Or if it is not appropriate (or feasible) to ask them, see what they are doing (and why they are not doing what you would like them to be doing) and then go fix that problem.

2. Or, if you don’t have customers yet, run a focus group on a sample of the audience you are targeting.

Either way, you want to really lose yourself in the process of understanding your customers’ needs, because that’s the best thing you can do for your product – and ultimately – your business.

Sr. Director of Product Management and Head of UX at

Sr. Director of Product Management and Head of UX at

![6337460478_4fefdce1bd_z[1]](http://connecteev.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/6337460478_4fefdce1bd_z1.jpg)